Using unsafe in our Rust interpreters

a disclaimer:

This article garnered a lot of attention for my use of the word unsafe. Frankly it’s my bad for using terms like “debatably ethical” (in the original title) in a tongue-and-cheek way when it’s in fact hardly unethical: no one but myself is affected by potential unsafe bugs, as this post is just about a research project (with 1, sometimes 2 people working on it). I’m not a company, we have no users, I’m just working on my research on interpreter performance: and since performance matters, unsafe has benefits for me.

If you think I’m definitely abusing the unsafe keyword though, please let me know! Feedback is always appreciated and I’d love to avoid it you can provide potential alternatives.

what am i reading?

This is part of a series of blog posts relating my experience pushing the performance of programming language interpreters written in Rust. For added context, read the start of my first blog post.

In short: we optimize AST (Abstract Syntax Tree) and BC (Bytecode) Rust-written implementations of a Smalltalk-based research language called SOM, in hopes of getting them fast enough to meaningfully compare them with other SOM implementations. The ultimate goal is seeing how far we can push the AST’s performance, the BC being mostly to be a meaningful point of comparison (which means its performance needs to be similarly pushed).

As a general rule, all my changes to the original interpreter (that led to speedups + don’t need code cleanups) are present here…

…and benchmark results are obtained using Rebench, then I get performance increase/decrease numbers and cool graphs using RebenchDB. In fact, you can check out RebenchDB in action and all of my results for yourself here, where you can also admire the stupid names I give my git commits to amuse myself.

what have i been doing

I’ve mostly just been fixing bugs. I’ve been informed that having failing tests in your interpreter is in fact not advisable, so I had to be a good person and fix those. I did most of that… But I was also doing something I invented called “procrastination” where instead of doing the right thing, I work on the fun bits of my work instead: squeezing more performance out of my systems.

Real quick, if anyone’s curious:

- I fixed some major oversight in the AST that gave us like 40% median performance - it was frequently, needlessly cloning entire blocks. I thought that was a deep-rooted issue but it turned out not to be too bad a change, so that’s very cool for me.

- I improved the dispatch in the AST, which was overly complex. Pretty sure the biggest win there was that this allows me to initialize method/block frames with their arguments directly, while previously they’d get created with an empty

Vecand have arguments copied in them afterwards. - I implemented

to:do:(and friends liketo:by:do:) in the AST interpreter! which was so much more straightforward than it was for the BC interpreter). That’s like another 40% median speedup. - and other minor things I’ve already forgotten about.

Now that this is out of the way: this week’s post is about figuring out why we’re so slow (spoilers: I don’t, not really) and being evil by using unsafe (spoilers: I do that, it’s pretty easy).

why are we so slow?

My PhD supervisor recently added a bunch of the microest of benchmarks, designed to test out very basic operations: ArgRead does nothing but read arguments over and over again, FieldReadWrite just reads/writes to fields, this kind of stuff. And even on basic operations like these, som-rs is super slow: an ArgRead has a median runtime of 3.37ms on our fastest bytecode interpreter, versus… 49.23ms on som-rs. Something’s way wrong.

So I’ve been doing profiling to investigate which parts of our interpreters are slower than they could be. I focused on the BC interpreter for this job since it feels like it should be much faster. And for the most part, there weren’t really any clear answers1: we mostly seem to just be spending too much time in the interpreter loop.

I made a new branch why-are-we-so-slow and I started experimenting. I did a bunch of small changes that yielded a few % of speedups: for instance, I changed

let bytecode = unsafe { (*self.current_bytecodes).get(self.bytecode_idx) };

…to:

let bytecode = *(unsafe { (*self.current_bytecodes).get_unchecked(self.bytecode_idx) });

Using unsafe in Rust means you tell the compiler “I know what I’m doing”. The nice thing about Rust is that it nets you memory safety if you play by its rules, but they can be limiting: unsafe allows you to ignore them, at your own risk. It’s generally not recommended… but it has its uses.

We were using unsafe since we were storing a pointer to the current bytecodes in the bytecode loop for fast access, and it was safe because there’s always bytecodes to execute. Which made me think “we’re already using unsafe, might as well also call get_unchecked for more performance”: this code never fails as the bytecode index never increases past the number of bytecodes in a function. That’s because the final bytecode in a method or a block is always a RETURN of some kind: if a method doesn’t return anything explicitly, it returns a self value, and the bytecode loop goes back to the calling function.

Theoretically a JUMP could increase the bytecode index to an incorrect value, say 100000… but here’s how I draw the line for optimizations: I choose to believe that my bytecode compiler is trustworthy, and that any code that is unsafe based on that assertion is a valid choice. I could be shooting myself in the foot since there may be bugs in my compiler, but I think trusting it is a fair assumption to make: it’s been proving sturdy enough, and if the bytecode I generate is incorrect, my code will fail miserably (or maybe act clearly incorrectly, but we’ve got many tests to check for that).

So it’s a choice between not trusting my compiler + maybe failing “elegantly”, or trusting it (by using unsafe) + maybe failing with ugly segmentation faults. And I choose the option that gets me the most performance, so unsafe it is!

unsafe frame accesses

Trusting the bytecode compiler means that whenever our bytecode requests a given argument, we know that this argument does in fact exist. Which means that when we currently look up an argument with this code:

pub fn lookup_argument(&self, idx: usize) -> Option<Value> {

self.args.get(idx).cloned()

}

…if we know that the bytecode we emitted is correct, then this get will never fail: we will always get an argument.

So it now becomes:

pub fn lookup_argument(&self, idx: usize) -> Value {

unsafe { self.args.get_unchecked(idx).clone() }

}

…and code that used this function, which looked like lookup_argument(0).unwrap(), can now ditch that unwrap(). We’re no longer using Option<Value>, but Value directly.

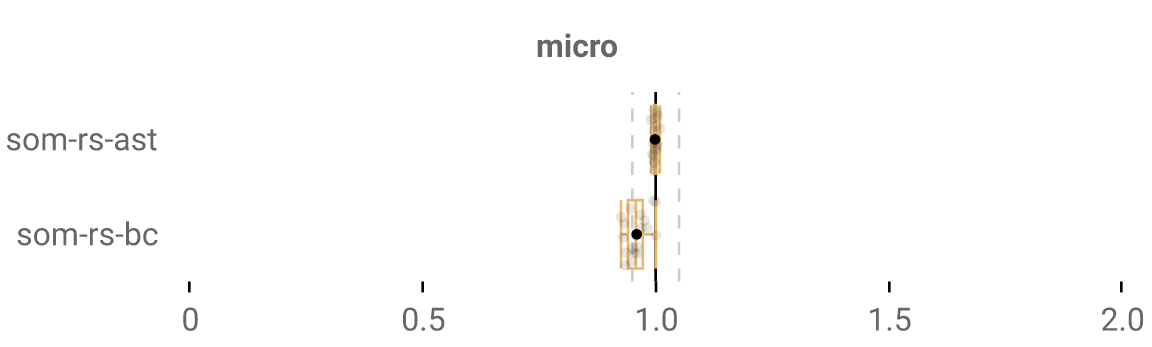

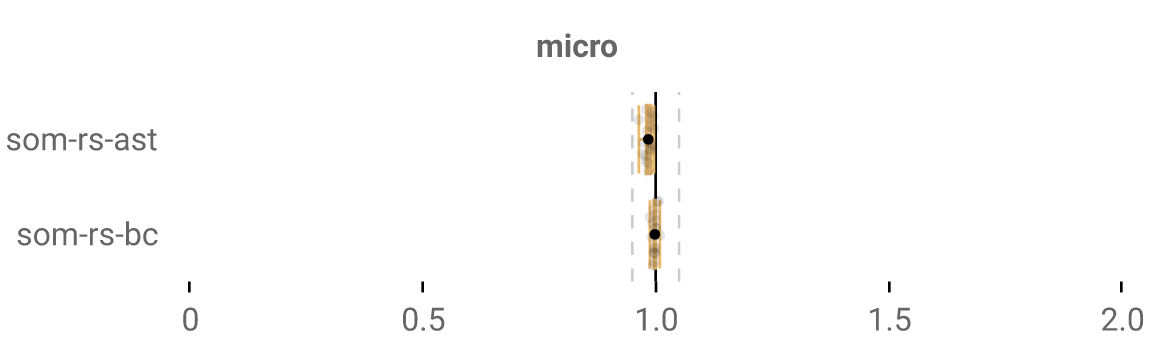

So that was a very simple change I had little faith in: “it’s just avoiding a couple of minor runtime checks”, I thought. The new code would obviously be faster, but I didn’t think it would be much faster - like 1% at best, maybe. Turns out I was wrong:

That’s a 5% median speedup from changing, like, 3 lines of code. Damn. Apparently those .unwrap() and get() calls add up.

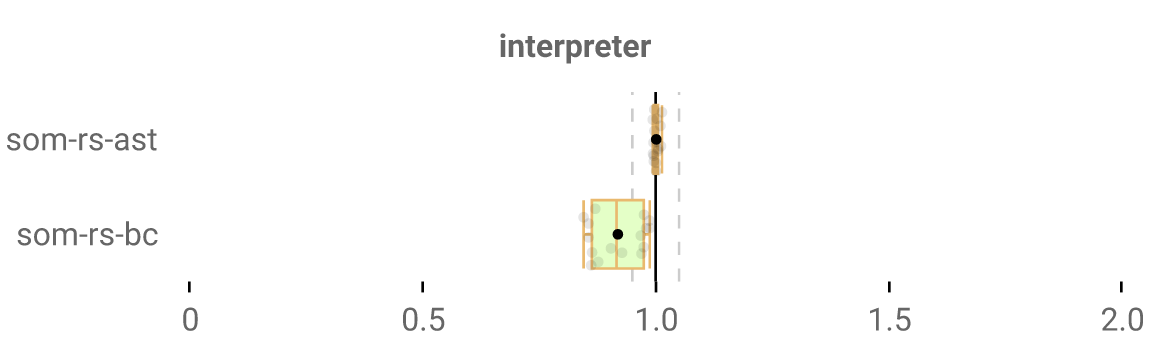

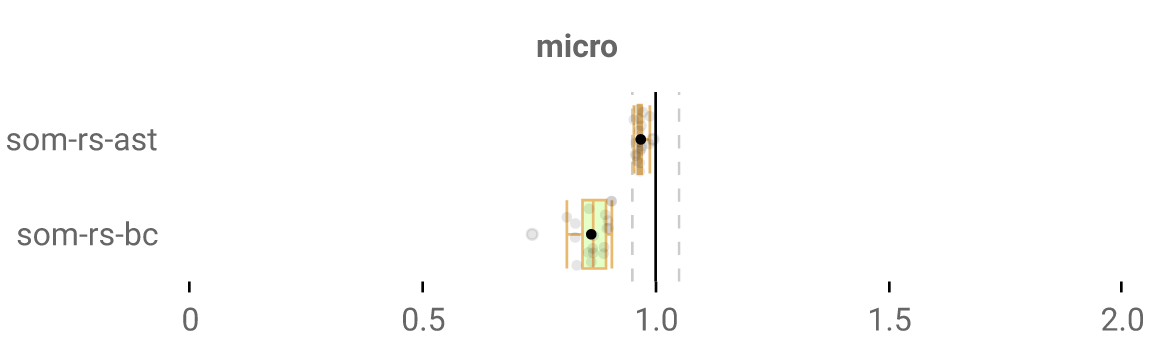

Which opens a lot of possibilities! Why stop at arguments? Let’s make local variable reads/writes get the same treatment, and same for literal constants (e.g. accessing string literals from a method). Here’s the speedup compared to the branch that already has the argument change:

Sick. I feel like a proper Rust programmer, using unsafe as God definitely did not intend (but he seems powerless to stop me).

I also optimized field accesses in the same way, but that wasn’t much of a speedup overall since those are less common.

unsafe bytecodes

If we’re doing unsafe stuff in the bytecode interpreter, we might as well focus on optimising some bytecodes directly. For that, I need to find out the most interesting bytecodes to optimize. So I did some basic instrumenting using the measureme crate to be able to print a summary of which bytecodes take up the most execution time.

The biggest offenders are SEND_X bytecodes: pretty much everything is a method send, so those get invoked a lot. Not sure they can benefit enormously from unsafe though, sadly, experimenting there didn’t yield much.

We have other targets though. Since we’re a stack based interpreter, we do a lot of calls to POP. It looks like this:

Bytecode::Pop => {

self.stack.pop();

}

stack is a Vec, and the code for Vec::pop() looks like:

pub fn pop(&mut self) -> Option<T> {

if self.len == 0 {

None

} else {

unsafe {

self.len -= 1;

core::hint::assert_unchecked(self.len < self.capacity());

Some(ptr::read(self.as_ptr().add(self.len())))

}

}

}

Unsurprisingly, it does several things we don’t need:

- it checks that the length is not 0: we trust our bytecode, and so this never happens in our world - if there’s a

POP, there’s something on our stack. - it checks that the length is inferior to its capacity: …I’m not sure why? It’s not like the capacity could ever be inferior to its length. At least I don’t know how our code could ever produce that.

- it wraps the output in a

Sometype: we know there will always be an output, we don’t need anOptiontype. - it returns an output in the first place: …we don’t even need to know the output!

So really what we want is just:

Bytecode::Pop => {

unsafe {self.stack.set_len(self.stack.len() - 1);}

}

I’d do self.len -= 1 like they do, but len is unsurprisingly not public. That would be an odd software engineering decision if it was.

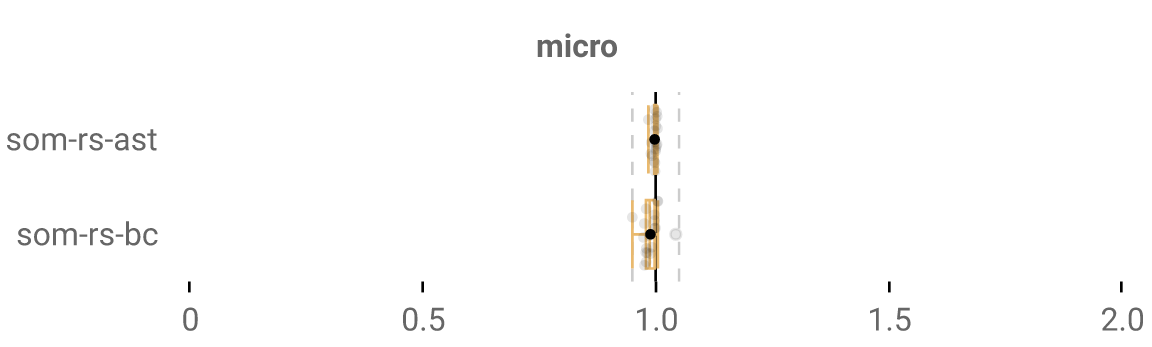

Speedup from that:

Hey, we take those. We can do a similar thing for our DUP bytecode (another common one), which duplicates the last stack element.

Bytecode::Dup => {

let value = self.stack.last().cloned().unwrap();

self.stack.push(value);

}

We trust our bytecode etc. etc., there will always be a value on top of the stack, so we end up with this:

Bytecode::Dup => {

let value = unsafe { self.stack.get_unchecked(self.stack.len() - 1).clone() };

self.stack.push(value);

}

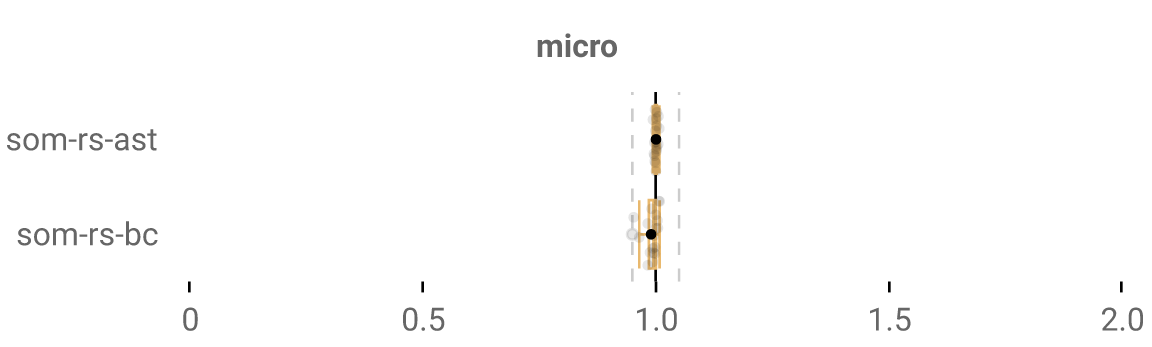

Man, I wish I had access to a last_unchecked() function, that’d look prettier. Speedup from that:

Not much at all, but we also take those.

I also spent a bit optimizing random bytecode that had very similar stack operations with peppered uses of unsafe. Speedup from that: pretty much none (oops). There’s definitely more potential for unsafe in our interpreter, but you need to identify the right targets. Ideally I’d find good uses for it in the SEND-related code, which I haven’t so far. I’m thinking that I should check the emitted IR/assembly for it to check for myself if it’s as fast as it could be, and more easily identify potential optimizations. Maybe in a future article.

unsafe frame accesses in AST also

That was all in our bytecode interpreter, but we can use unsafe similarly in our AST interpreter. In fact, we got some speedups from unsafe in the AST in my last post, so we know it benefits from being an evil programmer.

So I implemented all those unsafe frame accesses in our AST as well:

It looks underwhelming, but I assume that it really did bring a similar speedup. It’s just that the AST is much slower than the bytecode interpreter at the moment, and so that it wasn’t as big a win comparatively. Those performance wins might also only show themselves as they combine with other future optimizations.

final minor cleanups

These get_unchecked_mut and whatnot are nice, but they also make Rust crash unceremoniously, so I’d like to have the option to keep the original not-unsafe code. Rust offers the debug_assertions preprocessor directive to check whether we are in a debug version (my normal use case as a developer) or release version (fully optimized, the version we assess performance on) of the interpreter. So through cool Rust syntactic sugar, I can do this:

pub fn assign_local(&mut self, idx: usize, value: Value) {

match cfg!(debug_assertions) {

true => { *self.locals.get_mut(idx).unwrap() = value; },

false => unsafe { *self.locals.get_unchecked_mut(idx) = value; }

}

}

If we’re in the debug version, we call unwrap(), otherwise we call get_unchecked_mut. Really the debug version should have better error handling than just a dump unwrap, but I don’t want too much complexity from managing two versions of the interpreter at once. At least this code makes me sleep better at night.

Neat. Final numbers:

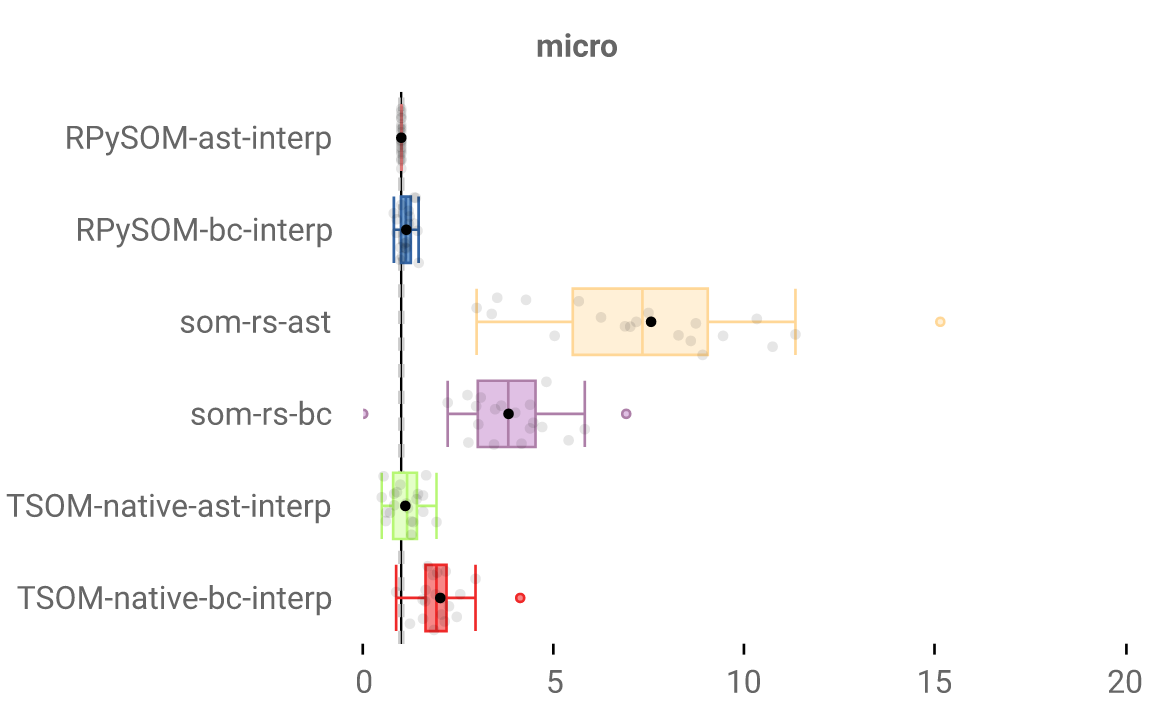

And since it’s been a while since I last showed that: here’s where our Rust interpreters currently are compared to the others!

Getting closer! If compared with the numbers in my first blog post, there’s been a lot of progress.

what have we learned?

To no one’s surprise, unsafe code is faster since you can remove safety checks. That’s a no brainer, but I did not expect it to be to that extent: an unwrap() might be extremely cheap, but several thousands of unwrap() calls aren’t.

Importantly, those changes were minimal: it only took me a couple of minutes and a couple of braincells to get acceptable speedups! And I highly doubt this only applies to my interpreters.

I think my usage of unsafe is reasonable. The Rust doc says to use unsafe when you know code is actually safe, or to do low level operations. But I can’t ensure my code is fully safe, and I don’t need unsafe for my interpreters to do what I want them to. I’m in it for the performance, and for that I’m doing a third secret thing where I assume my compiler did a good job and therefore that my code is safe.

I’ve not explored every possibility in this article. Hoping to find more as I go on profiling my systems and realize “hey, what if we just used a pointer there instead” or “yeah I don’t need the safety check there”. Though I want to use unsafe sparingly, since I lose on the benefits of Rust by using it.

And why are we so slow? Not sure yet, unsatisfyingly. But not using unsafe as much as we can is apparently part of the problem.

Thanks for reading, goodbye, xoxo and whatnot

-

only for the most part. I know what else is slow in my bytecode interpreter: I’m hiding things from you. I know we’re close, but we’re not that close. ↩